The forced Oblivion

Lóublie forcé (Ongoing)In 1939 with the declaration of war by France against Nazi Germany, the Minister of Colonies, Georges Mandel, demanded the transfer of 75,000 Indochinese wor- kers to support the National Armaments Industry. By this time, the French government had an Indigenous, North African, and Colonial Manpower Service (MOI) attached to the Ministry of Labor, which had the right to recruit colonial labor in times of crisis.

In 1942, fifteen trips were made between Indochina and France to bring more than 20,000 men over. Around 10% of these men came voluntarily, hoping to build a better future for themselves and serve the colonial French power. The remaining 90% were forced into mi- litary service on the European Front. These are the lives of the men this project focuses on.

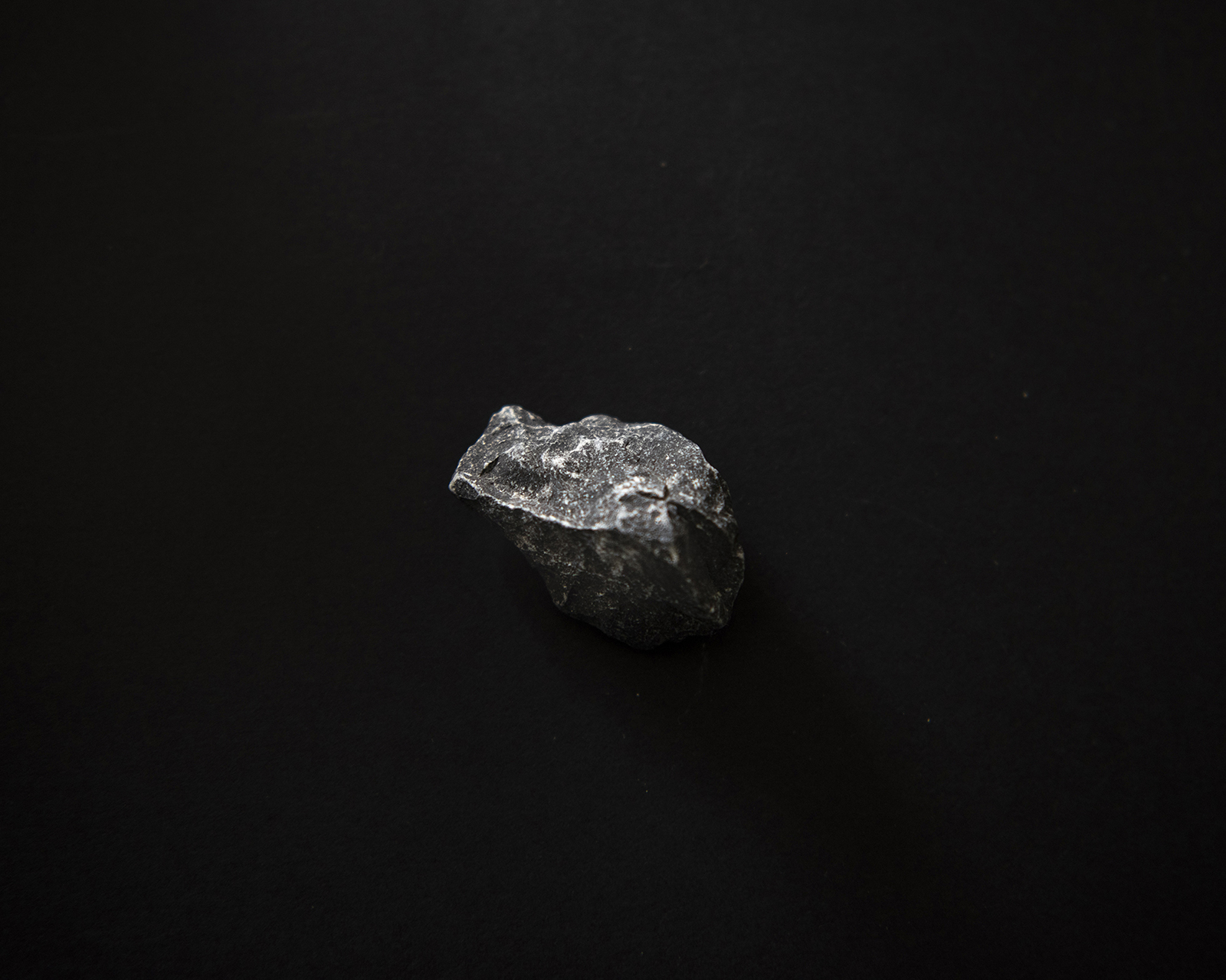

The men arrived in the port city of Marseille and spent their first nights in the building that today houses the notorious prison of Les Baumettes. In the coming days, the 20,000 men were scattered throughout the country; some were sent to work for the explosive industries in Normandy, others in the rice fields and salt fields in the Camargue, others in the coal mines in Lorraine and yet others in the forestry exploitation in Aveyron. These Vietnamese workers were considered hard-working and efficient but not fit for active military conscription, a job that was given to men coming from Algeria, Senegal, and Madagascar.

The living conditions of these men were precarious.

Their houses were simple wood barracks and lacked

basic services. They also were not provided with health

care. The workers’ 50 Francs salary was never honored,

leaving them with 1 Franc per working day. As a comparison, in France in 1942, unskilled French-born laborers

earned between 80 to 90 francs per day. To the lack of

proper housing, health care, and meager earnings, the

Vietnamese workers also endured daily racism.

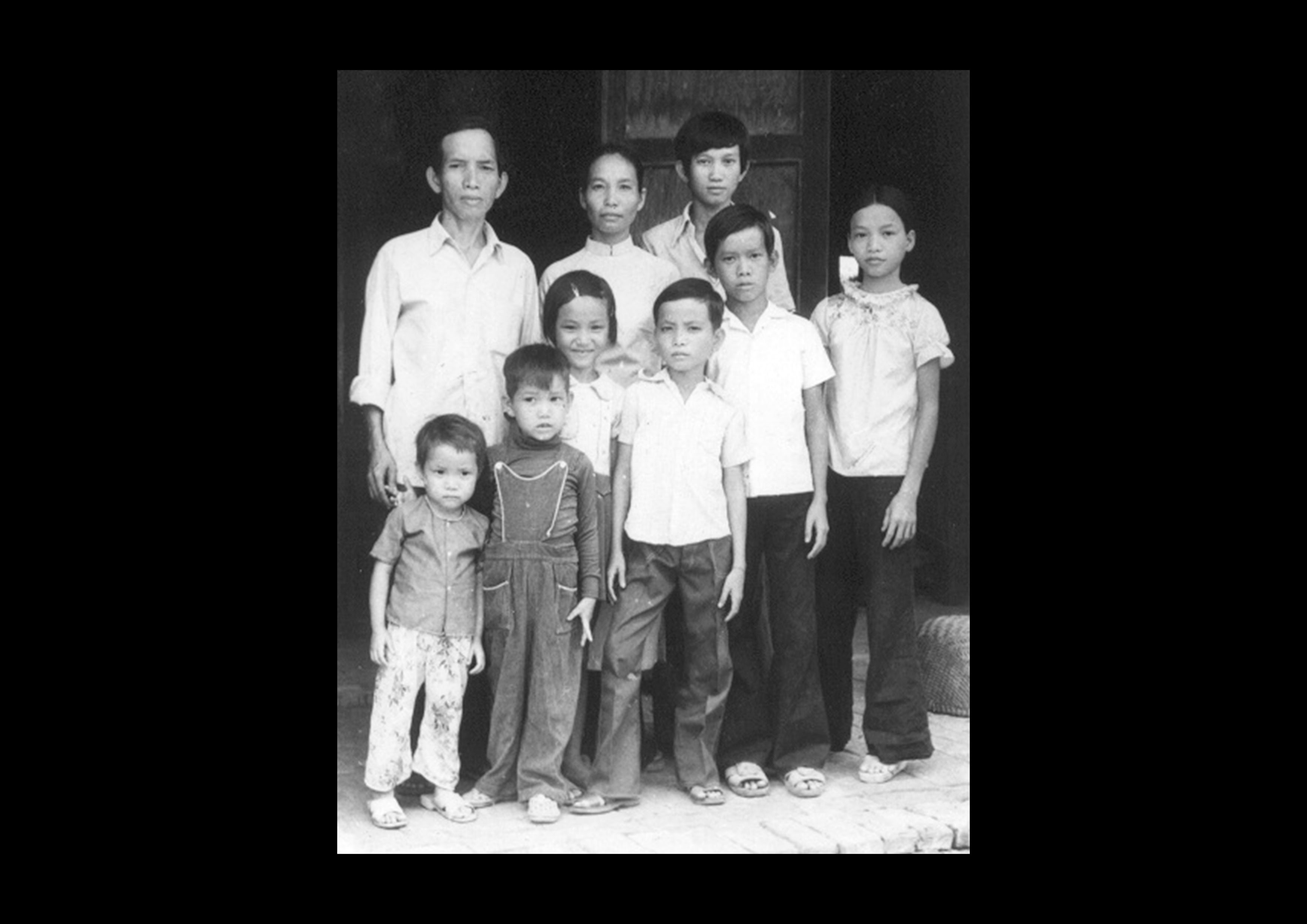

In 1945, at the end of the Second World War, the French government committed to repatriating all workers back to Vietnam. However, in 1946 the Anti-French Resistance War broke out, assigning the French navy fleets to defend the French colonial power in Indochina, leaving the workers stranded in France. 4100 men were able to transfer back to their country, but 15,000 men were left waiting in limbo for over ten years in France. They formed connections and started families during their prolonged wait.

The lives of these men happen between two wars and two continents. This work is an account of how the French colonial power forced thousands to work and live in degrading conditions under the pretext of a colonial racial discourse. These 20.000 stories began with a forced migration that later turned into a forced exile. They are 20,000 stories of lives that were minimized, forgotten, and hidden by the perpetrators and the workers themselves. For these men’s families, the circumstances of their lives remain partially unknown because of the trauma of living and working in such degrading conditions under a racist colonial power.

︎︎︎︎Overview

In 1945, at the end of the Second World War, the French government committed to repatriating all workers back to Vietnam. However, in 1946 the Anti-French Resistance War broke out, assigning the French navy fleets to defend the French colonial power in Indochina, leaving the workers stranded in France. 4100 men were able to transfer back to their country, but 15,000 men were left waiting in limbo for over ten years in France. They formed connections and started families during their prolonged wait.

The lives of these men happen between two wars and two continents. This work is an account of how the French colonial power forced thousands to work and live in degrading conditions under the pretext of a colonial racial discourse. These 20.000 stories began with a forced migration that later turned into a forced exile. They are 20,000 stories of lives that were minimized, forgotten, and hidden by the perpetrators and the workers themselves. For these men’s families, the circumstances of their lives remain partially unknown because of the trauma of living and working in such degrading conditions under a racist colonial power.

︎︎︎︎Overview